The NEU Report - Bringing CCIS to the Top

This is the third in a multiple part document originally written in 2015. The first post can be found here, the previous post can be found here, and the next post can be found here. This report has been adapted from a word document.

Bringing CCIS to the Top

Table of Contents

- Executive Summary

- The Introductory Course

- The Over Focus on Mathematics

- Math Overview and Applications Course Outline

- Concepts, Identification, and Applications of Mathematics

- The Bad Courses

- Theory of Computation

- Programming Languages

- The Hunt for Great Professors

- The Qualities of a Good Professor

- Qualitizer Results

- The Hunt Continues

- People in Specific

Executive Summary

The computer science school is facing a huge amount of competition from online courses, self-taught people, and coding bootcamps.

Although the bootcamps are often derided by the academic institutions that they are trying to threaten, there are noteworthy high profile endorsements (President Obama, Peter Thiel)

Beware Peter Diamandis’ ‘6 Ds of Exponential Growth, which illustrates an innovations rise from obscurity to take over. In that chart, bootcamps, much like online courses, are in the ‘deceptive’ stage, where it looks like they won’t work, and will never work. With enough time and effort however, they may very well pass into the ‘disruptive’ stage, where they take over everything. In 2015, 16,000 students are projected to graduate from a coding bootcamp, with courses costing around $11,000. For the price of half a semester at Northeastern, a student may find themselves just as well prepared as a CCIS graduate. (http://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2015-0608/coding-boot-camp-enrollment-soars-as-students-seek-tech-jobs) It’s possible that bootcamps will not take off, will be proven ineffective, and the unaltered computer science curriculum will live to see a glorious ten more years without having to adapt.

But what if that’s the wrong bet, and the College of Computer and Information Science ends up on the wrong side of history? The College of Computer and Information Sciences should consider the following:

- Restructuring the Introduction to Computer Science course to take advantage of the way that computer science has progressed in the last few decades, with a focus on doing scientific testing on the environment and the libraries used

- Replacing Scheme and Racket with more modern languages like Python or JavaScript

- Investing in the creation of a Survey of Mathematics course which aims to educate students on how to identify when a real problem belongs to a certain branch of mathematics, as well as the core concepts in those branches

- Either redoing the Theory of Computation course or making it non-mandatory

- Restructuring the Programming Languages course, 6. Creating an industry outreach program designed to attract top industry talent to professorship roles.

We will look into each of the above recommendations in detail, with the reasoning of each section explained as clearly as possible. The goal is many-fold: To keep the school from falling into obscurity or otherwise losing its stature, and to make it, and the university at large, a pioneering institution, able to witness and adapt to the changing tides the future brings. To this end, it is worth re-evaluating the computer science curriculum and the courses it is composed of. We begin our survey with the introductory course.

The Introductory Course

This course is hostile. The structure is such that the goal is to fail as many people as possible. This elitist atmosphere, that the computer sciences are only for the enlightened few is the most egregious sin committed in the whole school.

The course is overly difficult, and focused on distilled theory. There’s nothing wrong with theory, but some of the way concepts are introduced are bizarre.

What’s just as odd is the choice of Scheme (or Racket, as they refer to it now) as a learning tool. The language is esoteric and has outlived its usefulness. The old guard will argue vehemently otherwise, and may even dismiss the whole report at this point, but don’t let them drag the whole school into irrelevancy.

The creator of Scheme, Dr. Gerald Sussman retired the language for use in the MIT CS curriculum in 2009. He is cited as saying that the language was created to solve the problems of a certain era, and that since we no longer face those problems, and instead face new and different ones, that a new teaching method is needed to address that. The language they’ve chosen to represent that new method is Python.

The problem is that the idea of what constitutes computer science has evolved.

At one point in time it used to be the science of computation – the exact methods of reversing a list, how to store and retrieve data efficiently, how to properly use registers to do computation as efficiently as possible. It was a very slow process, done by thinking out the problem, thinking out the solution, and then writing a program, and writing it only once. This is occasionally and affectionately referred to as “hammock driven development.” If you could think out the problem well enough, you could solve the problem before you even so much as wrote a single line of code.

That is not the world we live in anymore. Not least of the great improvements to our discipline is the advent of extremely fast CPUs that allow us to test rapidly. If it doesn’t work, change what you think is wrong, and execute again. Repeat. In the time it would take an old programmer to think through and solve the problem, a modern programmer can solve 20 or 30 of them by the sheer benefit of having a fast processor with which to rapidly test changes.

The science has moved from having a deep understanding of the machine at every level to being able to perform the scientific method upon your libraries, environment, and platform. Computers have grown so complicated that we cannot understand them anymore.

Furthermore, and more pertinent towards programmers, the libraries we use and depend on, are often inscrutable. If the library is closed source, forget about looking into it. And if it’s open source, it’s probably too complicated to actually understand anyway. Often they have functions and subroutines that are deeply intertwined in each other, or are too complicated to comprehend without comments and there are of course, no comments, or bits are compiled by the computer and are thus not human readable.

So the state of the art has gone from knowing every detail to knowing zero details. Enter the scientific method.

The cycle of hypothesis, experimentation, observation, and recording. This is the basic science that we have to perform on the libraries now. We download a program with the expectation that it or its functions do what it says it does (hypothesis), we test our assumptions on some small sample data (experiment), we look at the results and see if it does what we thought it should have (observation), and we make note of that, mentally or otherwise (record).

If we are careful scientists, or just particularly savvy people, we try the same experiment again (reproducibility), and then again under slightly different circumstances. Often we’ll find that the functions that worked in one scenario blow up in another. If we’re good at being scientific, we can isolate the situations where it works from where it does not.

This is the state of the art. We can no longer know the inner workings, and we can only observe and experiment.

To say that this is “improper programming” and that “computer science shouldn’t stoop low enough to deal with this kind of problem”, or that “our CS graduates will produce better programs than that” is to miss the forest for the trees. No one is saying that this is an ideal. Far from it. Merely that this is how computers work now, and we need to embrace that.

Dr. Sussman did. He understood the need for this new kind of methodology, and it is one that we also should impart unto our students.

Let’s change the introductory courses – remove Scheme and its variants from the curriculum and reevaluate what’s truly important for new students to learn. The aim is not to fail them and weed out the undesirables, the aim is to teach as many of them as possible, to make them productive and capable.

Should they know how to reverse a list? Probably. Should they be doing it in Scheme? No. How about being exposed to algorithmic runtime analysis? Yes, but not in the introductory courses. And every effort should be made to properly introduce and instill the scientific method into our students in the context of their environment and libraries. Nothing is more critical than that one fact, regardless of in what language it’s taught in or how impure it feels.

The Over Focus on Mathematics

The criteria for entrance into the school of computer science is tough – high quantitative SAT scores, a track record for success in the higher maths available in high school, and an analytical mind. And then it continues into the curriculum. A student in the computer science degree path takes calculus 1, calculus 2, statistics and probability, and linear algebra.

No doubt many of the concepts taught in these courses can be useful, but it’s hard to not ask that timeless question that students have been asking since math became standard education: “When will we need this?”

In the case of calculus, that’s a really good question. Most computer science graduates will go on to do nothing requiring the higher forms of mathematics in their daily jobs, and an argument can be made that knowing these upper level calculus topics does not make one “educated”. But holding that argument aside, what in specific is this curriculum addressing? What types of work do the architects of this degree imagine the student body to be doing which still demands intimate knowledge of continuous functions?

The best arguments can be made for probability and statistics, and to a lesser extent, linear algebra, which is useful to be aware of because matrix manipulations can be useful in a number of computer science topics, including algorithm development and big data analysis. Statistics is useful no matter what discipline a student takes up, and probability has some applications, although it’s such a tricky subject that simply being exposed to the topic for a semester is likely to accomplish nothing in the long term for a student.

Given the fact that Northeastern’s attractiveness is in how the university instills students with practical knowledge, and the skills to solve the problems of tomorrow, the emphasis on these higher mathematics is somewhat misguided. The intent is good, but the end result is self-defeating. The goal should ultra-practical, not ultrastandardized.

There is much more to computers than simply mathematics. Furthermore, being good at math is not, despite common belief, a prerequisite. Language is the second half of software. If one has an aptitude for the natural languages, if one can speak and write, and convey ideas, then one can comprehend the computer sciences. How come our courses do not reflect this?

The heart of the problem was alluded to earlier – many of the topics of those courses are very useful, but the entire semester of those topics is a waste of time. In this case, the whole is not greater than the sum of its parts. Furthermore, with the immense resource that is the internet at all of our fingertips, and with wonderful and mature tools like Wolfram Alpha or Mathamatica, we have the ability to rectify this issue while simultaneously achieving the ultra-practical mandate our students expect from us.

Proposed is a new course that accomplishes a few basic goals:

- To expose all students to the important branches of mathematics, and their most core concepts

- To provide students with the understanding of exactly the kinds of problems these mathematics are perfect at solving, including ways to apply these ideas and solutions

- To teach students to identify exactly when a new problem falls within a branch of maths they have studied

- To teach students how to find solutions to these new problems, and if it’s a new branch of math they do not recognize, how to teach themselves what they need to know

- To teach students how to use Mathematica and Wolfram Alpha to solve the problems they encounter.

Given that Wolfram Alpha is capable of solving the most complex calculus a student is ever likely to learn in school, it would behoove everyone if they could spend less time learning the details of integration, and more time learning how to solve the problems they need to solve.

Combined with the idea of post-graduate services from Document #1, this course could be constantly evolving to keep students and graduates alike in touch with the ever changing tech landscape. The next section lists in detail the outline of the course.

Math Overview and Applications Course Outline

We begin this section by turning to a paper by Wrouthton and Cole at Northern Kentucky University, available at http://www.amstat.org/publications/jse/v21n1/wroughton.pdf

In their paper they understand that recognizing and differentiating between mathematic distributions (binomial, negative binomial and hypergeometric) can be tricky. In an effort to better teach students, they have uncovered methods that succeeded in boosting students’ ability to recognize these distributions.

What we are discussing here is not distributions, nor are we interested in their methodology, only that recognizing and distinguishing is critical skill, and is often a hard problem to solve. That their experiment dealt with mathematics is an unintended but fitting coincidence.

This proposal is the product of thinking about the nature of mathematics, and the nature of our technological world. Although many school administrators will respond with vitriol, defiance, or just plain indifference, it’s a truth of university that the moment students take their exam, they forget almost all of what they learned. We should instead focus not on teaching the facts, but teaching the skills to identify and understand, and to make them last. It was assumed that some kind of similar course would have existed already, but it was not the case. After surveying many of the technical schools (MIT, Olin, Carnegie), many of the great liberal arts schools (the seven sisters colleges, Wesleyan, Cornell, Reed) and others, it was found that no such precedent existed, which was very surprising. Therefore, this suggestion is composed almost entirely of original thoughts.

Concepts, Identification, and Applications of Mathematics

- An introduction to the theory of the course and its values. (Week 1)

- The changing nature of the world and how good our powerful and accurate computers are at mathematics

- The idea that we should free up our mental effort to focus on more complicated or unique problems. We should be able to identify the same calculus our parents solved, but we should know how to tell the computer to do it.

- The tools that are exceptionally good at this in particular

- Wolfram Alpha

- Mathematica

- Matlab

- Python libraries

- Examples and hands on uses of these platforms

- The concept of being able to identify any math that a student comes into contact with (with examples)

- The concept of being able to distill a math problem from a real world problem, and how often math is buried underneath a seemingly innocuous exterior (with examples)

- The ability to look at a problem that is obviously mathematical, and be able to identify that a different branch than is being used might be more appropriate.

- An explicitly stated objective that a student can identify problems that belong to maths they were not introduced to in this course, and the ability to self-teach and solve them

- Self-Research

- A promise by the university and the professors to help out (see Document #1, Post Graduate Services)

- An explanation that each unit will consist of the following:

- A brief history of the field

- The problems the field was created to solve

- Motivation for learning: the problems that the field is currently being used to solve (they might not be the same as the original intent of the field)

- The most important concepts of that field, the most genius or useful equations or ideas

- What characteristics make it obvious that a problem belongs to that field, or a particular equation within it

- For each major problem, a practical worked example in Wolfram Alpha or Matlab, showcasing just how much work the computer is capable of doing for us

- Unit 1: Calculus (weeks 1-2)

- Unit 2: Euclidean and Non-Euclidean Geometry (weeks 3–4)

- Unit 3: Linear and Matrix Algebra (weeks 5-6)

- Unit 4: Probability (weeks 7-8)

- Unit 5: Statistics (weeks 9-10)

- Unit 6: Topology (weeks 11-12)

- Unit 7: Algorithms (clustering, neural, probabilistic) (weeks 13-14)

Throughout the course, the primary objectives are to inspire, motivate, and give students the skills to solve and identify these branches in the real world on their own. A heavy emphasis is placed on performing worked examples, while teaching students exactly how to use the tools of the trade. By the end of the course, students will be experts in the three main tools, and will have an understanding of mathematics that will last them a lifetime longer than a traditional education.

As many as 50 years ago, MIT used to famously tell their students that the students at other schools will be able to put them to shame when it comes to solving the problems that matter today. They shouldn’t despair however, because when tomorrow, and all its associated problems comes around, MIT graduates will be the ones putting everyone else to shame because they have been trained to think more generally and with the future in mind.

This course is Northeastern’s rebuttal to that. Northeastern students, just as much or perhaps more so than MIT, can solve the problems of tomorrow. Let’s encourage that. Not by forcing our students to solve the problems of yesterday the way we solved them yesterday, but to think about the problems of the future and the ways to approach and solve them with all of our modern resources.

The Bad Courses

There are two courses in the computer science curriculum that stand out as having either outlived their usefulness, or haven’t been given enough attention.

Theory of Computation

At one point in time, it seemed like this course was a natural fit for the degree. Finite State Automatons and context free grammars have their place in the hierarchy of the computational sciences, but so do compilers, and yet we do not require compilers as a mandatory course.

The course seems significant for historical reasons rather than practical ones. Rarely, a person is encountered in the real world outside the walls of academia who speaks highly of learning about these grammars and creating their own state machines, but they always emit the aura of one who would be more comfortable with a university professorship rather than an engineering job.

Simply put, the course is lacking in the most important factor: Motivation. What are the uses of this course? In what way will being able to produce an unambiguous context free grammar and a deterministic finite automata assist the student? If it is possible that this case can be made, then the professors need to do a much better job of explaining it unto the students. As it is, this course is one of the most dreaded in the curriculum.

Further, the course has one cannon textbook: Introduction to the Theory of Computation by Michael Sipser. Recalling a conversation from Document #1 about online courses allowing student to learn at their own pace, this singular textbook is a disaster for the course. It is dense, thick, full of abstract math that is difficult to grasp except for the most logically inclined among us, and isn’t very user-friendly.

If a student isn’t one of the chosen few who can clearly grasp the book, then they are out of luck because there’s only one book, and thus there’s only one real way to learn the course. This is not an acceptable way to teach the course. If there exists only one way to explain the material, and that one way is difficult even for the best students, then the material doesn’t deserve a spot on the mandatory course list.

We can think this one through in the following way. Things worth learning are learned by a lot of people, but are also taught by a lot of people. For what reason has the material become so standardized? Perhaps there have been no advancements made in the field, and thus it doesn’t need an update? Perhaps the book and its author are such sacred ground that attempting to re-do the material would be tantamount to academic heresy? It could be any number of reasons, but the important fact is that across all universities, Sisper is the accepted way to teach the material, and that is a travesty of what education should be. Students are here to learn, and this is not conducive.

Just as poor for the state of the course is the fact that, at Northeastern, it is taught by a small cadre of professors, some of whom have been around for many decades. When speaking of the sin that is having very few ways of teaching a course, this is cardinal among them. In order to bring a course and its concepts into the modern era, new blood is not optional. These long-served and great professors understand the subject matter well, but they often suffer from the Curse of Knowledge. Steven Pinker, legendary linguist and Harvard professor, in his new book Sense of Style suggests that the Curse is manifested as being so involved in the details and the minutia, that things that are obvious to an expert are obscure to everyone else. Further, the Curse is like a fog that clouds the ability of the expert to concisely and properly explain those concepts to an audience who is unfamiliar or uninitiated. The result is that the Expert cannot properly filter between important concepts and unimportant concepts, and cannot explain the concepts that they do end up discussing well enough.

This is not an indictment against any professor in specific, nor against professors in general. It is a remark about the necessity for fresh, energetic people enthusiastic to inform new generations about an important subject matter.

It is strongly encouraged that Northeastern do extensive research into finding new professors who are eager to teach these concepts and are capable of bringing their motivating enthusiasm to the class. Until then, keeping the course from the mandatory curriculum is recommended.

Programming Languages

The College of Computer and Information Science has a heavy investment in the general expertise associated with programming languages, including a graduate level research department headed by a number of influential professors in the field. This is a big deal for the school, and they should press their advantage in this area.

It is in this context that it is depressing to look upon the flagship course, which manages to not only not feature brilliant professors, but to also miss the point of its namesake. The contrast of what the name invokes and the reality of the course was made stark after having personally conducted research on what many top ranked computer science programs offer for their version of the course, as well as having sat in on the open hearings for the candidate deans of the college and questioned them on this subject two years ago.

The course begins with an introduction to what a programming language is, what the components of a language are, and what it needs to do to be considered a complete language – and then students are thrust headfirst into the experience. Create context free grammars, parse the language syntax, and build into it core functions that make it usable. Students in this course essentially take a gutted version of Scheme and flesh it out bit by bit into a more thorough version. Project based, yes. But that alone does not make it a good experience.

This course is afflicted by many of the same complaints that affect computer science as a whole – it is misnamed, and students are being done a disservice by this fact. The programming language course is one of the many courses in the university designed to select the next round of laboratory assistants and PhD candidates. These classes have their place, but it would be prudent to turn them into non-mandatory classes.

At other schools, this is an overview course, and it generally consists of 3 pillars:

- What makes any given language good or bad? What are the aspects of long running languages, and how they did they become so widespread? Was it due to luck and time and place, or was there something more fundamental about the language? What makes a language “Mature”?

- What is the history of languages? How did we get to this point, and which languages didn’t survive the cut?

- What is the future of languages? What can we learn from the past to inform our choices into the future, and what are we learning now that will influence how we make the next generation of languages?

As an addendum to these 3 pillars, an additional 2 are proposed here for Northeastern’s inclusion in this hypothetical revised course:

- What were the great ideas in languages that we lost somewhere along the way? What we have now is so far from the apex of language design that some good ideas produced from deep understanding must have been forgotten, including from such antiquities as VB3 and APL.

- What is the role the development environment plays in the language? Is a language without a good and usable environment actually a good language? Visual Studio is the standard for developing with .NET languages. How much influence did it have in bringing Microsoft’s languages to the forefront in the last decade? And if Eclipse had been better, would Java have obtained a dominant position earlier in its life? Would it have been better equipped to maintain that position?

As some professors at the College have put it, “few people would agree that the state of the programming languages course is ideal.” Just as is the theme of Document #1, so too is it with Document #2. There are many opportunities for Northeastern to take, they only need be taken.

The Hunt for Great Professors

I’d like to make this section a bit more personal, and single out a handful of professors who have had an impact on me, and who I believe have the potential to usher in a new era of domination and prosperity for the university.

First on the list is William Clinger, a professor who teaches both Object Oriented Design and Software Development. Though prone to making a poor first impression, he’s incredibly talented and takes pride in teaching students properly. Many students fail to see past the brusque exterior and write him off as haughty, but don’t let that fool you. Between his knowledge of the intricacies demanded of software engineers in the real world and his detailed understanding of some of the more theoretical aspects of computer science, Professor Clinger represents an ideal blending of the type of theorycraft and handicraft the College should look for.

Pete Manolios, teaching undergraduate Logic and Computation, as well as numerous graduate level courses is among the finest professors in the department. At first brush, his interests and his courses seem to be overtly theoretical. Simply talking to him however, reveals that he is about so much more. He understands that his work in the theoretical, like most work, should be in service to a greater, useful goal. One of the first assignments in his Logic and Computation course is to write a paper, hardly what a bunch of incoming CS freshmen were expecting to do, on some important aspect of computation, and his specialty, verification, in the real world. His lectures are often peppered with anecdotes about the perils of unverified code in the wild, and how they can lead to critical failure. He enjoys his research, but he also enjoys the idea that he has “customers”. His work is for some practical purpose, of use to someone else. This perspective is a good focusing lens, forcing him to have aim, to trim the excess, and to deliver a result.

Steven Intille, a professor who moved from MIT to Northeastern, has done wonders for the College – jumping immediately into doing important things. Not only is he building a world class research group at the intersection of the health sciences and information technology, he has a relentless focus on doing things that work, with a strong dose of theory to both propel the projects forward and to be the rock upon which those projects are built. His exploratory Google Glass course was composed of carefully measured amounts of problem identification, out of the box thinking, and proper use of the literature in the field of health/IT to help really understand the issues at hand.

Next is Kathleen Durant, who came from the world of professional healthcare to teach the Database Design course. Professor Durant is more of an engineer than a theorist. She came with her own motivations, having seen the unfathomable wreck that is the present state of databases and other information technology in hospitals. Healthcare, it seems, has no shortage of people who see opportunities to do better. She taught us the history of databases and as much of the core concepts as we needed to know, then it was off to the races with project design. She most likely inherited a syllabus, but she approached the course thoughtfully, understanding the goal – to create better designed, longer lasting software, and to teach us, her students, how to do it.

Finally is Nik Bear Brown, a large man who embodies, at least in some ways, the stereotype of the programmer at google. But that description, the google engineer, is an unjust one. Homeschooled and self-taught, Professor Brown has the deepest knowledge of theory of any professor I have ever met, and yet is not blinded by it. During his Algorithms course, he was always on the ball, constantly changing and adjusting his lectures to fit to the abilities of the students, and always looking for ways to shake up the explanations in order to find the one that made the most sense to the most students. He impressed upon us the goal of having us be able to explain core concepts at any chance encounter in a coffee shop to people who aren’t necessarily computer scientists. This touches upon some recent science, indicating that true understanding is roughly measurable by being able to deliver an explanation to a 5 year old child. And whenever the theory became overwhelming, he would dip into motivating examples, trying to get us to understand just why and where these bits of knowledge would be useful. Not least of all, his way of approaching projects, with constant checkups and a very openly expressed desire to not just assist during the course, but after, when the course is over, was refreshing.

The common threads between all these professors are plain to see. Their desire to teach students, not just to fuel their laboratories and quest for research grants; Their ability to impart the right knowledge, to filter out what is necessary and what is not; and the mix of theory and pragmatism, knowing that the end result of any effort should be to create a working product.

It is these professors who set the gold standard for professorship at the College. If Northeastern could build up a staff composed even 10% more of people like them, the school would see a disproportionate rise in the quality of its graduates. The question is then, how can Northeastern find and hire these people?

There exists a subset of teachers at all schools, especially the ones in the Boston area, who are very inclined towards these real-world practical solutions. The University need look no farther than MIT, as that’s where the University’s own Steven Intille came from. Since he’s moved here he’s started many ambitious programs and new courses dedicated to solving problems. The first approach is to simply ask these professors what drew them here, and what could be done to draw more likeminded people. Though this approach may seem too straightforward, the answers to these questions will likely produce some very clear, if unexpected, results.

The second approach was touched upon in Document #1, and it had to do with identifying the professors at other universities who have a demonstrated history of teaching solutions and problem solving in their courses, or who have established or participate in a number of groups outside their office and lecture hours dedicated to similar pursuits.

In the case of the world class schools like MIT and Harvard, there are bound to be a number of professors who must feel as though the bureaucracy has become stifling, or that being at the top universities affords them little opportunity to impress or go against the grain. These professors are the lowest hanging fruit, and can be enticed easily with offers of being able to do great things at Northeastern, and doing those things in new and innovative ways.

Regarding people who aren’t professors anywhere and have no presence in academia, consider an industry outreach program. This program would not only find and identify people of interest in the industry, but would also send the first message and establish a dialogue. The goal of the program, finding new and interesting people, is not to take them away from their work, but to offer them a bonus. The critical aspect is that the university is not offering them a full time position, nor are they being offered enormous financial rewards. These people do not want to become professors, have no desire to ever be on a tenure track, and need none of the financial or medical safety nets that a university position offers. They have good jobs, and they want to tell young people about the world and the problems they have encountered and how to solve them. In return for them imparting their knowledge, these professionals get first dibs on potential talented recruits. Of course, a position like this exists somewhat in the Adjunct Professor position, whereby someone has another job – but this program is aimed towards very proactively finding and recruiting people of a specific type of talent – the ability to lecture well and teach about the technologies, techniques, and theory.

For locals, it would be trivial to invite them to the university, or to send a representative out to meet them. The latter might even be more important, because these people are guaranteed to be professionals and have little time to spare for an unproven opportunity. Showing that the university is willing to expend its own resources to meet them on their own time and territory is a very important step. The first communications should simply be an email stating that Northeastern has identified them as interesting, and would love to chat about potential opportunities at the University.

The email should contain nothing heavy; as many questions as possible should be fielded by a representative in person. Subsequent communications, after the first meeting, can be handled in email or in person as both parties see fit.

The Qualities of a Good Professor

In specific, here is an analysis of what to search for when looking for good professors from the outside. This section hopes to make clear some values that are often associated with good professors, potential or otherwise.

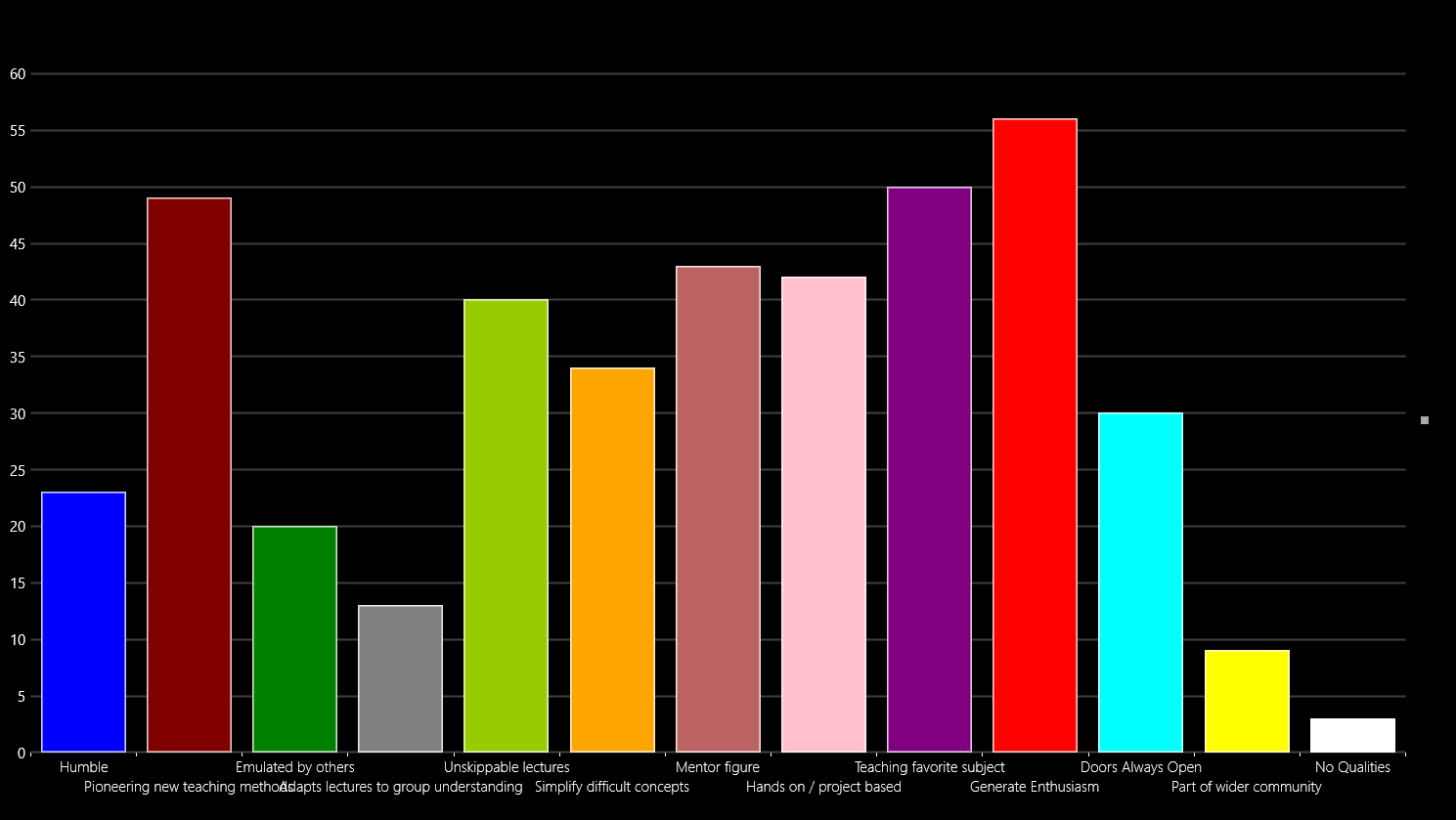

This analysis is based on a collection of 105 recipients of the MacVicar award, which bestows MIT professors who are extremely gifted educators with a $100,000 grant. The breakdown is in terms of common ideas expressed by and about those professors during their award acceptance speeches and MIT news articles. Having read through the articles multiple times, the following ideas and attributes stood out among many of the laureates.

Personal Attributes:

- True passion for the subject they’re teaching, and not just a deep knowledge

- Being a mentor or showing a sincere interest in students outside of the classroom

- Having a “doors always open” policy towards office hours

- Doesn’t overly brag about how great they are

Teaching style:

- Attempting to pioneer new ways of teaching -Having their style or innovations become widely emulated at the university or beyond

- Adapting their lectures in real time based on the students’ understanding / displayed collective confusion

- Having lectures that students actually want to attend, or making lectures that don’t feel like lectures

- The ability to simplify difficult problems, and guide students towards deeper understanding

- Teaching with hands on research, or having a project based curriculum

- Inspiring students and generating enthusiasm

Other:

- A presence outside the university in activities related to the subjects they teach inside university

Before we discuss the results, I’d like to digress on the methodology.

After collecting each MIT press release about the MacVicar awards, and then splitting the relevant text for each recipient into individual files, the data was combed through, looking for common themes expressed by the professors. This is where the 12 qualities above came from.

After having that basis to start from, it was time to do the raw data collection – which involved going through each professor’s text and noting down which qualities were exhibited. This was done by hand, with a list of the qualities on a piece of paper, and a growing number of Roman numeral tallies by each of those qualities. For every quality a professor was felt to have expressed, another tally would be added to that quality. About halfway through the collection, it became clear that a critical error had been made. Occasionally, the text for a professor would be long enough that the same quality would strike me as being expressed more than once. But because of the length of the article, and the simplicity of the record keeping, that quality would sometimes get tallied twice for a single professor. This meant that the data was corrupted, and the results could no longer be trusted. This was bad science.

This lead to the creation of a tool which was originally supposed to only be simplistic and for my own purposes, but has since burgeoned into a much more general purpose data and idea management device. The result is what I call Qualitizer (articulateinsights.com/products/qualitizer).

This tool allows a user to input a list of any number of elements, along with between 1 and 12 qualities they feel are associated with that list, and then provides a very quick and easy way for the user to go through the data, “qualitizing” each element according to their own criteria. The following data is the result of using Qualitizer on the set of professors.

A note on the data:

Many of the nominations, especially from the late 90s, were barely a single line in length, meaning that some professors had almost no qualities to record. Furthermore, since the qualities recorded are for those which are explicitly stated or clearly implied in their nominations, the criteria for meeting a quality is somewhat strict. As a result, it is best to view the data as a low floor for the skill and characters of MacVicar recipients, that most professors will probably exhibit every trait to varying degrees, and that the professors are likely far more impressive than they might seem from just judging their individual data points

Qualitizer Results

Total Data Points: 107

Total Qualities: 12

| Quality | Observations | Percent |

|---|---|---|

| Generate Enthusiasm | 56 | 52.34% |

| Teaching favorite subject | 50 | 46.73% |

| Pioneering new teaching techniques | 49 | 45.79% |

| Mentor | 43 | 40.19% |

| Hands on / project based | 42 | 39.25% |

| Unskippable lectures | 40 | 37.38% |

| Simplify difficult concepts | 34 | 31.78% |

| Doors Always Open | 30 | 28.04% |

| Humility | 23 | 21.70% |

| Emulated by others | 20 | 18.69% |

| Adapts lectures to group understanding | 13 | 12.15% |

| Part of Wider Community | 9 | .41% |

Generating enthusiasm ranked highest, with 52% of all recipients being praised with this quality. This isn’t very surprising. Students learn best when they are excited about the material, so it be unexpected that the best teachers are those are can best inspire their students. Plus, there may be some selection bias. The only professors who would be nominated for an award would be those that have enthusiastic students. That being said, this is a quality that shouldn’t be dismissed – far too many professors at Northeastern and other universities are lethargic and don’t seem very interested in their subject, let alone in teaching.

What is surprising is how high pioneering new teaching methods ranks – coming in at third place with 45% of all recipients showcasing this quality. To explain, this means that a professor invests much of their time, and has been successful, in looking at the concept of education from both higher and lower levels and producing new ways of teaching. This ranges from innovative use of props, to creating new alternative and supplementary video lectures, to thinking deeper and letting their methodologies be guided by scientific principles and new research. That so many teachers at MIT spend much of their time trying to find the optimal way to get students to learn is one of the reasons that MIT students are so smart. Their students aren’t necessarily smarter – they are simply taught better.

Teaching Favorite Subject is a compound trait – counting for both a professor who is teaching his favorite subject, and for a professor whose favorite subject is teaching. This is an indication of the passion that is conveyed to the class, and is different from their ability to generate enthusiasm. A professor’s level of interest in the subject, although certainly contributive towards enthusiasm, is more about the professors understanding, and ability to convey that understanding. What is interesting about this quality’s second place rank is not how high it ranks, but that it confirms that great professors really do love what they do.

The most desirable trait turns out to one of the rarest – coming in second last with 12%, adapting lectures to group understanding is understandably very difficult. This is a sort of on-the-fly revision and editing process. Professor Nik Bear Brown described above can do this very well. This kind of thinking requires that the professor really be quick on their feet and capable of breaking away molds and static lecture notes. Finding the explanation that makes the most sense to the most students, and doing it differently for each class and lecture, might be the holy grail of professorship qualities – possessed by only the most elite.

When searching for great professors – it couldn’t hurt to be guided by these qualities. They represent what MIT believes to be the pinnacle of professorship.

The Hunt Continues

These MacVicar laureates represent not just those who are brilliant professors, but those who are also brilliant in their fields. They consistently demonstrate a mastery of their discipline comparable to the geniuses who helped establish them. One professor was even directly compared to Richard Feynman. The idea that a great educator is usually incapable of being a leader in their field is not an often repeated criticism, and just as well, because it would be mostly untrue anyway. Far more dangerous is the widespread belief that great innovators and knowledgeable researchers also make acceptable lecturers. Not “great”, or even “good”, but merely acceptable. Even this is untrue - most researchers make for very poor educators. Great care should be taken to limit how many of them are forced to teach to students.

Another thing to note is that people often conflate personality and magnanimity with being a good educator. There are people, for instance, who have glowing reviews on RateMyProfessors.com, a site that lets students contribute anonymous reviews of professors online, who are not very good at imparting the right kinds of knowledge, or who even have toxic influences.

In the search for great professors, it is then important to understand that the best people might not always be described in the most positive of lights. Sometimes, mixed or even negative sentiment, might be more informative.

People in Specific

In terms of finding those in-industry professionals, there are people in Boston and beyond who would be more than willing to not just give a guest lecture or two, but to, with the right offer, come in and teach a more permanent course. REDACTED formerly of REDACTED and presently of REDACTED, comes from an academic background, possessing a PhD. A brilliant software engineer, he gets to work on complicated big data analysis of genetics. He would most likely relish an opportunity to do some work with an undergraduate community, were he enticed enough to work it into his schedule.

Another potential recruit includes REDACTED, an elder computer scientist from the days of yore who, among many other things, wrote Multics-based software. He is a man of enormous untapped potential, who loves nothing more than trying to educate and discuss with his coworkers on the intricacies and history of old systems and languages, and the proper way to approach the sets of problems he and the company he works for face.

Boston is likely to have the single greatest concentration of brilliant, first generation programmers in the world. It should be a top Northeastern priority to find and hire them.

Continue to Document #3 - Survey of MOOCs